All by definition

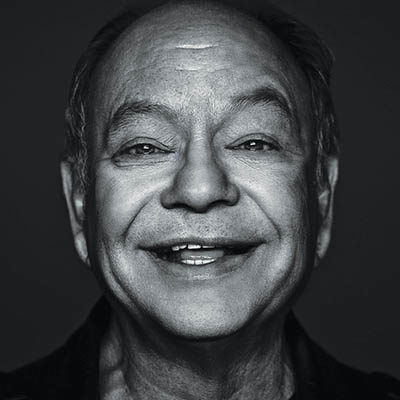

A conversation with Cheech Marin

“Soy Chicana”

Cici Segura Gonzalez

Standing at the entrance of the record-breaking exhibition at Philbrook Museum of Art, “Papel Chicano Dos: Works on Paper from the Collection of Cheech Marin,” giant vermillion-colored block letters splashed upon a midnight background proclaim:

“CHICANO ART IS AMERICAN ART.”

—Cheech Marin

“That’s one of the end stories I’m trying to get out there,” Marin said, “so that people get used to that idea. And the more you say it, the more you show them. Then they get it.”

Although he laughingly refers to himself as “an artist of philosophy,” Marin’s commitment to art cannot be overstated. He has established a reputation as an art collector over the last four decades and has used his celebrity to expose the world to another form of popular culture: Chicano art. Since his first acquisition in the 1980s, he has amassed approximately 750 paintings and has shown various installments of his collection in over 50 established museums, from Los Angeles to the Smithsonian and internationally in Spain and France.

Tulsa is the latest city to host a cross-section of Marin’s growing trove.

Jake Cornwell: You began referring to yourself as a “Chicano” early in life. Progressively, the term has evolved from a negative connotation to a term of endearment. What do you believe defines the school of Chicano art?

Cheech Marin: I’ve never considered Chicano art to be a derogatory term because my father, who died in ’92, always called himself a Chicano. And I’ve always referred to myself as a Chicano—once I heard the term and found out what it meant, I thought it was the thing that described me. I never ever associated myself with being a Hispanic or even Mexican-American. I never liked those kinds of hyphens.

Cheech Marin: I’ve never considered Chicano art to be a derogatory term because my father, who died in ’92, always called himself a Chicano. And I’ve always referred to myself as a Chicano—once I heard the term and found out what it meant, I thought it was the thing that described me. I never ever associated myself with being a Hispanic or even Mexican-American. I never liked those kinds of hyphens.

[Chicano art] is evolving as we speak, as it has its whole history. Speaking at this point, it kind of rotates around what “who is” or “who isn’t”—mostly who is—Chicano. I think the definition is expanded as we see who’s involved in the process, vis-à-vis Mexican and Central Americans.

Cornwell: Your collection has traveled all over the country and to Europe. When you heard a bunch of Okies were interested in Chicano art, what was your response?

Marin: I said, “Well, good for Okies! It’s about time.” I always viewed Okies as intellectual Texans anyways (laughs).

Cornwell: In what ways is Chicano art reflective of the community it comes from?

Marin: Well, we are individuals and we have a worldview that is both Mexican-influenced and Latino-influenced, and American at the same time. American pop culture, and where they coincide and mesh together, is what forms Chicano art.

What these artists are involved in is giving you not a minute-by-minute, step-by-step, inch-by-inch explanation of community; what you get is the sabor—or the flavor—of what that community is like and represents, and how it feels. It’s a much more well-rounded, 360-degree feeling of what the state of the art is.

There’s more and more artists coming into the arena all the time. We’re now on our fourth or fifth generation of Chicano artists that are coming up and have their own identity. And they all comment on the community that they’re involved in. It’s a very fast-moving and wide-ranging field.

Cornwell: Is Chicano art a social commentary on issues of the day?

Marin: What I’ve noticed is that a new generation of young guys, young painters, come into the area, [and] their first comment is on the social condition of their community. That’s been happening over and over and over again. Once [they make] their statement like that, they get their bona fides. And then they do whatever else they want in art. I mean, you can be a Chicano who paints, or you can be a Chicano who paints “Chicano school,” which is involved in commentary. But it is always involved in the state of the community at some point in their careers.

Cornwell: Viewing art is sensorial and can produce an emotional experience. What is it about Chicano art that made you want to preserve these pieces and become the Chicano art guy?

Marin: I recognized it was well-done art. It was art by painters who really could paint. Because I’d been studying paintings just about all my life, when I discovered these Chicano painters, I said, “These guys are really good.” It’s like discovering a great musician. It doesn’t matter what kind of music he is playing, but you hear it when it’s really, really good—and on tempo and original and new and full of vitality. I felt when I first discovered them that they were not getting ... the shelf space they deserved and recognition within the American art process. So, that kind of became my goal. And then my mantra [became]: “You can’t love or hate Chicano art unless you see it.” So, my journey or my quest was to get as many people to see Chicano art as possible.

Cornwell: Why do you think it took this long for Chicano art to be accepted in mainstream art?

Marin: There was a certain mindset of what American or avant-garde art should look like. And the Chicanos, we’re just coming into the beginning of the influence and the introduction of Chicano art. That’s because they didn’t have the long history of having art in museums and art backers that build museums and put their art in there. We’re starting into that process right now.

Now, [Chicano artists are] firmly established as fine artists. At the beginning they were kind of viewed as a prop folk art. They’ve evolved way past that, and they’re all fine artists now. I love the folk element in some artists and I want to encourage that as well. It’s all by definition. It’s redefining the definitions of “what is” and “what isn’t,” and so I think we’re going to be very much involved with that process.

Cornwell: You’ve compared picking a favorite painting to choosing a favorite child—it’s just impossible. But, is there a particular purchase that is especially meaningful?

Marin: I remember one Frank Romero painting I got. I was doing a movie and they really didn’t have enough money to pay me for what I wanted. Part of the payment was in art. It was okay by me!

Cornwell: Where do you see the collection in five or ten years, or even after you’re gone?

Marin: I’ve been given this museum in Riverside, California, to house the collection. So, I kind of see it there—being in the center of Chicano art and culture.

Cornwell: Is there still resistance from the establishment to showcase such works, or is the old guard beginning to change?

Marin: No, no, there isn’t that much resistance anymore because we’ve validated it in all kinds of museums. Not only with the critical community, but with people in general. So, I think the message is to get it out there. And that’s what I’m trying to do.

Cheech Marin will be at Philbrook on Thursday, June 22, at 6pm. His talk is sold-out, but the “Papel Chicano Dos: Works on Paper from the Collection of Cheech Marin” exhibition runs through September 3, 2017.

.jpg)

.jpg)