Talent grabs back

Lady players share their experiences in the music scene

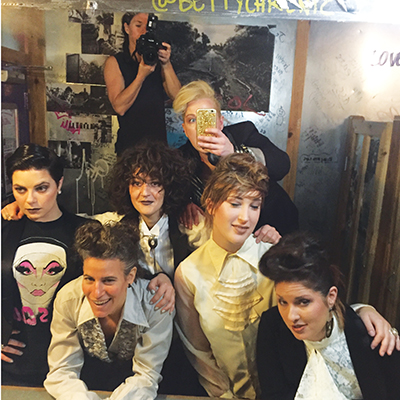

From left: Kristin Ruyle, Mandii Larsen, Kylie Wells, Andey Delesdernier, Amelia Pullen, Carmen Skelton

Melissa Lukenbaugh

“We should start a band, all of us together!” Amelia Pullen suggests.

Pullen sits in my living room, alongside five other women: Andey Delesdernier, Mandii Larsen, Carmen Skelton, Kylie Wells, and Kristin Ruyle, all of whom enthusiastically agree with her suggestion.

These women don’t all know each other, but they at least know of each other. In just 20 minutes—one cocktail and a few jazz cigarettes in—they’re already a squad.

This instant connection is partly a product of their gender (shout out to the sisterhood!), and partly a product of the art that drives them. They are all musicians: Pullen plays drums for Dead Shakes; Ruyle is a percussionist and live-wire entertainer for Count Tutu and Branjae and the Filthy Animals (full disclosure: she’s also my sister); Wells and Delesdernier are both DJs (DJ Kylie and DJ Afistaface, respectively), Skelton plays the fiddle and her “vocal box” in the bluegrass band Klondike5, and Larsen is a multi-instrumentalist who’s played for Broncho and Low Litas.

Tulsa has a number of talented frontwomen and singer-songwriters—Branjae, Fiawna Forte, Kalyn Fay, Rachel LaVonne, Brandee Hamilton, Desi Roses, Annie Ellicott, to name just a few—but the women in this room are bound together by their experiences as background players and supporting instrumentalists, or, in the case of the DJs, curators upstaged by the music itself.

Over pork skins and gin, these ladies trade stories about performing in a male-dominated local music culture.

“The thing is, when women get fucked with, it’s either undermining or sexual or both,” says Delesdernier, to a room of rowdy agreement. She mentions the time a dude hauled in a crate of records to the bar where she was playing, invaded her workplace and assumed he had a right to her equipment and her professional space. Of course, he didn’t.

Larsen recalls telling a sound guy which frequencies were feeding back in her monitor and receiving a resounding “fuck you” in response. (Skelton points out that she can’t remember ever working with a sound woman.)

Pullen tells of a gig during which a man in the audience stepped onto the stage and started adjusting her drums mid-performance while he mansplained that she needed to play her right side higher and adjust her snare.

Ruyle offers a similar anecdote—though in her case the man actually started playing her drums in the middle of the gig.

One has to wonder if these men would have felt so entitled to the space and gear of male players. Everyone in this room is willing to put money on the answer being “no.”

The conversation turns to politics. Inevitably, that Cheeto-dust-covered Vienna Sausage, Donald Trump, comes up. The room expresses anger and dismay at the recently released recording of Trump bragging about the ease of sexual assault.

Most of these women regularly endure and fend off unwanted sexual advances. Wells informs us that she carries a knife with her everywhere she goes; to this, several other women respond that they do, as well. Just in case.

Despite the sometimes-frustrating inequities they experience, none of these women would call themselves victims. They tell these stories matter-of-factly—they’re less complaining than sharing the reality they live in. They love what they do, and live for their art.

“I get my power from feeling good about myself,” Larsen says.

“I feel freer, like a queen. I’m on my game,” Skelton agrees. That sense of self-worth, for Larsen and Skelton, and these other women, is derived from making music.

Like most local musicians, they must strike a balance between evening performances and day jobs: Wells is a stylist, Pullen and Larsen bartend, Delesdernier freelances, and Skelton is a stay-at-home mom who moonlights as a seamstress and electrician.

Ruyle works full-time as an independent environmental and safety consultant, on top of the grueling practice and gigging schedule she keeps.

“I may be dreading going to a gig because I gotta play until 2 a.m. and be back at work at 6:30 a.m. for work, and I’m already exhausted,” she says. “But once I hit that first note … all of that is washed away. It’s the ultimate meditation.”

Tulsa’s music community is small, but bolstered by a committed fanbase, and in this conversation these women betray no desire to run to a bigger city.

“[I’m guessing] there are about five hundred hardcore music lovers that keep musicians alive in Tulsa,” Ruyle says, which makes for a tight-knit group often made up of familiar faces. People get to know each other, and the musicians they support. They get to watch the personal and professional growth of their favorite players, which provides an intimacy rarely seen in scenes with the impressive array of talent that Tulsa supports.

“We’re lucky because everyone knows each other, and everybody wants to help each other,” Pullen says. Wells agrees, pointing out that although it can take a while to prove yourself, “once you do, you’re gold.”

“[Tulsa] has given me a platform to be myself, and make a living at it,” Delesdernier says, something she wasn’t sure was possible ten years ago.

When asked to name a few female musicians that influenced her development as an artist, Delesdernier rounds out her list by naming Kylie Wells. “She was DJing when I was still making mixtapes…I was always like ‘she’s so fucking cool!’”

Wells is visibly moved by the compliment. She and Delesdernier pass the pork rinds back and forth to “crunch through their emotions.”

As the evening winds down and the interview goes off the rails, these women begin to share tricks and tips with each other. Pullen is having some shoulder problems, so Ruyle and Skelton immediately begin asking questions and offering advice, sharing what worked for them when they were dealing with injuries. Before you know it, Skelton is on the couch next to Pullen, looking for pressure points, and Ruyle is promising to get her in touch with a physical therapist she knows who specializes in treating musicians.

“Women who barely know each other are now giving tips on how to care for their bodies,” Delesdernier says wistfully. The room erupts into laughter and a collective awww.

For more from Amanda, read her article on the Oklahoma leaders of Moms Demand Gun Sense.

.jpg)

.jpg)